Editor’s note: As the University of Arizona School of Art moves closer to its 100th anniversary in 2027, we’re profiling former faculty and students.

Judith Greene Golden, a powerful voice in contemporary photography who taught at the School of Art in the 1980s and ’90s, engaged with themes of gender, identity, popular culture and the influence of the media.

Golden, who died on Jan. 27, 2023, at age 88, described herself as an “alchemist.”

“With the magic of photography, I transform reality into the mystical realm of myth, dreams and spirit,” said Golden, one of the early feminists working in self-portraiture, role-playing and media critiques.

When she retired from teaching in 1996, the university’s Center for Creative Photography honored her legacy by establishing the Judith Golden Archive, which houses a comprehensive collection of her photographic prints and archival materials and an online gallery of her work.

Judith Golden in 1992: Students hosting a “Patterns of Influence” symposium at the Center for Creative Photography took the professor and others out to “Downtown Saturday Night,” where Golden tried on various hats in a local antique shop. (Photo by Colleen Mullins)

Jacinda Russell, a 1999 MFA School of Art graduate in photography, learned about bookmaking from Golden and helped transfer the photographer’s slides to the CCP archive from 1997 to 1999.

“Judith’s method of artmaking was hands-on — a mixed media approach — something that is viable and sought-after today when people want to create outside the digital space,” Russell said. “She collaged, hand-painted, assembled and reinvented portraiture.”

Born on November 29, 1934, in Chicago, Golden was raised on the city’s multicultural South Side, an experience that sparked her lifelong interest in global cultures and human complexity. As a child, she took art classes at the Art Institute of Chicago, where she later earned her BFA in 1973 from the School of the Art Institute. In 1975, she completed her MFA at the University of California, Davis, studying under notable artists William Wiley, Manuel Neri, Roy DeForest, Wayne Thiebaud and Robert Arneson — central artists in the California Funk movement who instilled in Golden a sense of play and a need to mix mediums.

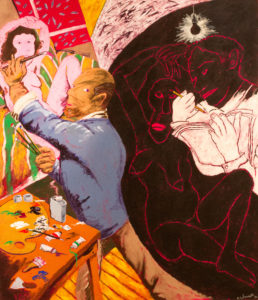

Judith Golden, untitled, 1975, Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona: 1979 National Endowment for the Arts Museum Purchase, © Judith Golden 1975

Golden taught at UCLA, where she worked closely with acclaimed artist Robert Heinecken from 1975 to 1979. The Hollywood influence of that time subtly shaped her visual style, blending traditional photographic technique with multimedia elements to offer a satirical commentary on celebrity culture and the constructed nature of identity.

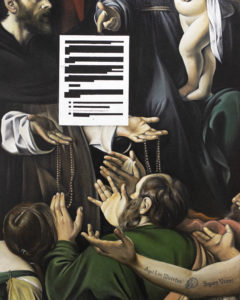

Her “Chameleon Series” included 50 three-dimensional, hand-colored self-portraits, which transformed her from a delicate woman into “tough street guy,” said Arthur Ollman, who organized Golden’s solo retrospective “Myths and Masquerades” at San Diego’s Museum of Photographic Arts in 1986. She did a series of movie posters, where she rephotographed posters from “B” films and replaced the heroine’s heads with her own. Golden also made some artist books, one of which copied pages from an illustrated Kama Sutra and the Hindu book on erotic love by Vatsyayana — incorporating her face in the place of some females.

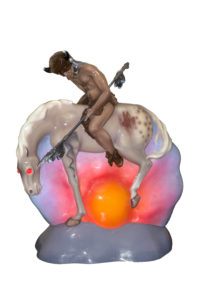

In 1981, Golden moved to Tucson to join the School of Art faculty. Immersed in the area’s rich Native American cultures, she began to explore spiritual and mythical themes, particularly the use of masks in ceremonial rituals — a motif that would become central in her later work.

“Her photographs during this period reflected a deeper, more symbolic approach, combining personal introspection with her unique take on cultural storytelling,” said Fern Martin, a Los Angeles producer and author who was Golden’s daughter-in-law.

Judith Golden, Juliette Man-Ray, 1979, Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona: Gift of Fern Martin and David Thomas Golden, © Judith Golden 1979

In 1990, Golden was awarded an Honorary PhD from Moore College of Art in Philadelphia, recognizing her contributions to both photography and arts education.

Golden’s photographs have been exhibited internationally and are part of prestigious museum collections, including the Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, the Museum of Photographic Arts in San Diego, and the Museum of Contemporary Photography in Chicago. Her work is featured in seminal texts such as “The History of Women Photographers” by “The History of Women Photographers” by Naomi Rosenblum and “Seizing the Light: A History of Photography” by Robert Hirsch.

“I was never one of her students, but Judith taught me a subject close to her heart … bookmaking,” said Russell, a retired associate professor of art who taught at Ball State University. “I learned many methods of binding, something I would take with me in both my MFA thesis exhibition and eventually the classroom in the years that followed. I would grow to love this medium and consider it is an essential part of my art practice.”

One of Russell’s jobs at the CCP involved scanning Golden’s slide collection — including the photographer’s “Ode to Hollywood,” “People Magazine,” “Julia’s Braid” and “Chameleon” series — and the task helped make Golden’s work memorable for years afterward.

Judith Golden, Carrot Top, 1988, Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona: Gift of Terry Etherton, © Judith Golden 1988

“It was the ‘Portraits of Women’ series that struck me though,” Russell said. “Judith photographed women in photography who were known at the time but would make an indelible mark in the future, including Barbara Kasten, Judy Dater and Susan Rankaitis.”

Throughout her life, Golden received numerous grants and honors, including support from the National Endowment for the Arts, the Arizona Commission on the Arts and the Polaroid Corp.

As an educator, Golden was “fiercely committed” to mentoring young artists, Martin said.

“Her decades of teaching at UCLA and the U of A left an indelible mark on generations of students, many of whom cite her as a foundational influence in their creative lives,” Martin said. “Her teaching combined technical excellence with a deep philosophical engagement with art as a form of social and personal inquiry. She insisted on a rich blend of technical expression and meaning in all finished pieces, no matter beginner or grad student.”

Martin said Golden was a “deeply loving and caring mother” who struggled as a single parent to balance her artistic and academic pursuits while trying to be a grounding presence to her family.

Judith Golden with former assistant Sue Van Horne, left, in Albuquerque. (Selfie by Sue Van Horne)

Golden is survived by her son, David, and daughter, Lucy, and grandchildren Julia, Joseph, Jonathan Joshua and Camille, and a wide community of friends, colleagues and former students.

“Judith leaves behind a body of work that speaks with clarity, courage and compassion — a legacy that will continue to inspire and challenge the way we see the world,” Martin said. “She was a fearless advocate for the truth and power of art and or constant reinvention of her art and herself.”

Fern Martin, Colleen Mullins, Arthur Ollman and the Center for Creative Photography contributed to this story.